In early March I spent 10 days in Israel during one of the darkest chapters in its history, and against the background of a global outbreak in anti-Semitism.

Shortly after my return — I was on a media study tour — I spent an afternoon with my father in his sunlit kitchen. We scrolled through photographs from my time away, pictures from Israel’s north, teetering at the edge of all-out war, and from Kibbutz Be’eri in the south, the site of one of the worst massacres on October 7.

There were joyous photographs too: one, an image ubiquitous in the country, featured an Israeli flag with a love heart drawn around the Star of David. The image had at first jolted me; it is the rhetorical opposite of the crossed out Israeli flag you might see plastered around inner Melbourne — a call to boycott the Jewish state and Jewish businesses, reminiscent of Nazi Europe in the 1930s.

My father smiled at the love heart photo. His memoir, Two Prayers to One God, recounts how in 1947 he and his father huddled by the radio in their home in rural Hungary as the United Nations voted to partition Palestine into a Jewish state and Arab state. At the end, they stood and hugged wordlessly. Then his father, my grandfather, went to the piano and began to play a strange tune “so mournful and stirring.” When my father next heard the tune it was as the anthem of an independent Jewish state, Hatikvah. The Hope.

That afternoon in his kitchen we talked about our hopes and fears for Israel. When, hours later, I got up to leave he said, “thank you — this was very special for me.”

A few weeks later he went into hospital. Ten days after that he died.

This was no ambush on the part of the universe. My father was 95, razor-sharp but frail, and like I said, 95. Still, ludicrous as it sounds, the day of his death came as a shock as if an early warning system had failed me.

His funeral was organised through the liberal synagogue. Dad was never circumcised; his family converted to Catholicism before the war in the hope of avoiding anti-Jewish discrimination. “It didn’t work,” someone in the crowd muttered as I recited my eulogy.

“With George’s passing,” I said, “the world loses yet another witness to the horrors of Auschwitz at a time of resurgent Jew-hatred.” He was lowered into a grave alongside that of my mother, Eva. At her burial 11 years ago, an Israeli flag was placed inside her coffin, in keeping with her wishes. She would often warn me, as many Holocaust survivors in the diaspora warned their children, not to get “too comfortable” in Australia. Because you might one day need to pack suitcases again.

**

I’m a journalist. I’m also a Jew. And I’m no longer the same Jew who went to bed on the night of October 6 feeling ominously comfortable with my place in the world, certainly with my place in Australia.

So when it comes to Israel I cannot affect neutrality.

Then again, a great many people aren’t neutral when it comes to Israel.

**

The moment you set foot in the Arrivals terminal at Ben Gurion International Airport a banner screams: BRING THEM HOME NOW! Behind the banner is an art installation of hundreds of dog tags hanging, as if suspended, in the air. As you take the ramp down to passport control on either side of you are photographs of hostages, their names and ages. When you reach passport control the biometric scanners each default to an image of a hostage, so that after the machine scanned my passport an image of Judy Weinstein, 70, an English and meditation teacher with frizzy hair and effervescent smile, flashed before me — and throughout my visit her image stayed with me as a soft rebuke, for while I could come “home” to the Jewish homeland, Weinstein, and the remaining 120 of the initial 253 Israelis taken as hostages to Gaza could not.

Weinstein, in fact, will never be coming home: she was reportedly murdered on October 7, one of the 1200 mainly civilian victims of Hamas terror. Her body is yet to be returned. It is unclear how many hostages are still alive.

Everywhere in Israel you go, the hostages shadow you, their faces pleading from T-shirts and bags, from every inch of every wall.

At “Hostages Square” in the forecourt of Tel Aviv’s Museum of Art an empty dinner table commemorates the taken. A weekly yoga class honours one of the kidnapped, Carmel Gat; released hostages told of her holding yoga classes for her fellow captives. On the day we visit, around 100 people are in solemn repose on their mats. In the far corner of the square, a man, a relative of another hostage, addresses a small gathering. When a civilian is abducted from their home, he says, the state has an obligation to bring them back “at any price.”

The slogan “Together We Shall Be Victorious” still booms from billboards and government buildings but each day the sentiment comes under greater strain. In March, the rallies for the release of hostages were tentative — small pop-up protests blocking the traffic, larger gatherings of several thousand on the weekends. “Please don’t call it a protest” one of the hostage relatives we met with begged of me. “We’re not criticising anyone.” Since then the demonstrations have grown in size, volume and intensity, targeting the Prime Minister’s residence, as police respond with horses and water cannon.

The IDF’s daring rescue of four hostages from Gaza in June failed to subdue tensions. Protestors are even seeking to undermine Benjamin Netanyahu’s scheduled address to the US Congress on July 24, demanding he first cut a deal for the hostages’ return.

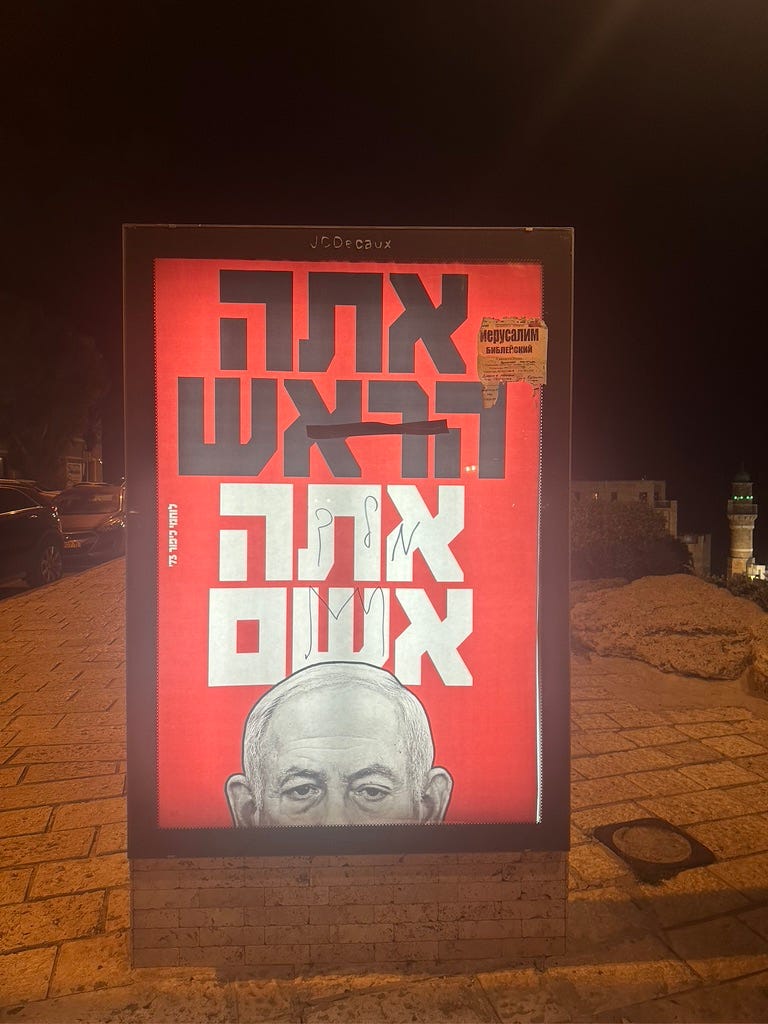

The hostages are the soundtrack to daily life in Israel: a persistent, howling pain, a drumbeat of outrage. Outrage at “Bibi” Netanyahu because in the words of a protest slogan he’s the leader so he is “to blame” for Israel’s calamity; at Hamas, for their curated sadism, and at the world, for its indifference to the fate of these tortured souls.

**

Our media delegation met with military and defence officials, independent analysts and veteran journalists, current and former politicians and government bureaucrats. Some of these individuals sit in Israel’s national-unity war cabinet and were handed urgent messages from staff as they spoke with us. We also heard from officials from the PLO and the Palestinian Authority; these interviews were organised by Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and sadly had to take place via Zoom. Since October 7, much of the West Bank is a restricted military zone.

Our briefings pre-dated Israel’s fatal strike on the World Central Kitchen aid workers in Gaza, its assassination of top commanders of Iran’s Revolutionary Guard in a building adjacent to the Islamic Republic’s consulate in Damascus, Iran’s retaliatory missile attack on Israel — the first ever attack on Israel from Iranian soil — and Israel’s stealth retaliation on Iran.

But from what I learned in Israel, and since, I reckon the nation’s political zeitgeist is best understood as a series of contradictory propositions, all of which can be true at the same time for that’s what rationality looks like in the Middle East. For instance:

The Netanyahu Government is broadly disliked, and distrusted because it is beholden to a coalition that includes far-right messianic racists. Yet the Netanyahu Government’s twin war aims of returning the hostages and eliminating Hamas enjoy broad public support.

Hamas only gives up hostages in response to Israeli military pressure. Yet Israel also faces what journalist Haviv Rettig Gur has called a “Sophie’s choice” of losing the hostages or losing the war against Hamas, which retains a critical stronghold in Rafah embedded among 1.3 million Palestinian civilians.

Israel confronts a lonely future of forever wars against rejectionists and jihadists. Yet Israel is edging towards normalising relations with a once implacable foe, Saudi Arabia, and stands to benefit from a moderate bloc of Sunni-Arab nations — the Saudis, the Emiratis, the Egyptians, the Jordanians, and even, maybe, at a squint, the Palestinians, under a reformed and more pragmatic Palestinian Authority, who might finally achieve statehood in the West Bank and Gaza at some time in the distant future once Bibi and his merry band of reactionaries and messianic racists have left the building.

No part of the above rosy scenario will eventuate if Israel inflicts more carnage on the Palestinians in Rafah. The above rosy scenario will only eventuate if Israel vanquishes Hamas — limiting the carnage as best they can — thereby bolstering the forces of liberalism and moderation against the forces of fanaticism and oppression everywhere, including on university campuses in the West.

**

The Jew, whether in Israel or elsewhere, will never enjoy what the father of modern Zionism, Theodor Herzl, called “normalcy.” The Jew will emerge from this present darkness, normalcy is just around the corner.

**

The Jews in Australia “have to fight!” said one senior Israeli official, in the manner of an avuncular coach, “fight in the courts!”

Some years ago two cousins of mine made aliyah, a Hebrew term for immigrating to Israel, its literal meaning is “going up,” an ascent to Jerusalem and therefore to a higher spiritual plane. Since October 7, one of them has taken over from where my mother left off, sending grave warnings via WhatsApp: “We’re very worried about you over there in the diaspora. Don’t wait till it’s too late! We’ll embrace you here with open arms.”

**

Many officials we met with said we were “brave” for visiting Israel at such a time. This was strategic flattery, obviously — even if rocket fire did trail us the days we visited the border regions. And even if my journo colleagues were exposing themselves to professional shaming by going on the trip; the Australian news site Crikey publishes a list outing reporters who’ve visited Israel over the years replete with photos of some at the Dead Sea, smeared figuratively in the mud of the Zionist entity.

But “brave” is the mother we met spruiking her start-up at a networking dinner in Tel Aviv barely five months after her son was slaughtered at the Supernova desert rave.

And when on October 7 the army mobilised reservists, so many overseas backpackers answered the call that El-Al had to put on extra flights from South America and Asia and even then people were sleeping in the cockpit and on the floor.

**

My father, mother and sister spent two years in Israel in the late 50s. They lived in Tel Aviv alongside other European migrants in a quiet street of newly-planted trees. My father secured a job at a psychiatric hospital in nearby Bat-Yam, my mother commuted to university in Jerusalem to study medicine, my sister settled into primary school. Life was good but my father couldn’t stop worrying about the next war; Israel’s only friendly border in those days being the sea. Wracked with guilt, my parents decided to leave for Australia; a decision my mother had resisted, and regretted to her last breath.

On their flight — their descent? — out of Israel on 10 December 1958, the Air France pilot announced: “Please look down after take-off and enjoy the night lights in Tel Aviv.”

My parents could not enjoy the night lights of Tel Aviv.

Maybe there is such a thing as intergenerational Zionist shame because, to be honest, when the Israeli officials said we were brave to visit, I was, in fact, flattered.

**

As a frequent visitor to Israel, I can boast familiarity with the kibbutzim, the agricultural communes lauded back in their heyday as the world’s most successful experiment in voluntary Marxism. Many times I’ve toured a kibbutz in the company of a proud elder who says, “here is the chicken coop, here is the pomelo orchard, here is the kindergarten.”

For a moment, as we gather in the communal hall at Be’eri, I let myself imagine we’re embarking on such a tour. A banner trumpeting the kibbutz’s 77th birthday still hangs; the milestone celebrated the night before October 7. A photographic display traces the kibbutz’s evolution from small outpost to a home for more than 1000 residents and Israel’s largest printing press. Many pictures of kids milking cows and running in sack races.

But today, Nili, a 50-year Be’eri veteran, leads us through a museum of horrors that began at 6.55 am on the Saturday when Hamas militants breached the kibbutz gates, and ended only the following Monday, by which time nearly one in 10 residents had been slaughtered and dozens kidnapped. Nili is grimly qualified for the task. Her mother was killed in the Japanese Red Army’s 1972 massacre of 26 civilians at Israel’s Lod Airport. And as a prison psychologist — her PhD is on incest offenders — she has never flinched in the face of depravity.

“Generally I listen,” she tells us, “but today I talk.”

Today she talks as fast as she walks. She carries a map of the kibbutz with the devastated areas highlighted in pink.

We walk past charred buildings. The remains of a kitchen; a dishwasher, the rack melted out of shape, spilling shattered plates.

In keeping with the kibbutz ethos, Nili tells a collective story of her brutalised community: here a father jumped from a second storey window with two children in his arms, here on the village green lay 200 corpses (residents and infiltrators), here 10-month old Mila Cohen was shot in the head in her mother’s arms. “Here is death row where, you know, house by house.”

Only later, and in passing, do we learn that Nili’s husband, Yoram Bar-Sinai, an architect, was also among the murdered — and that she, along with her daughter and granddaughter, miraculously survived.

She is wound tight, her narration inflected with sarcasm. The more than 100 infiltrators at Be’eri included Gazan civilians in search of loot — flatscreen TVs, mincers — with the slaughter an added bonus. “Is it better now?” she addresses them. “Was it worth it?”

The slaughtered at Be’eri were disproportionately left-wing peaceniks: people who had transported sick kids from Gaza to hospitals in Israel, run consciousness-raising tours along the Israeli-Gazan border, rallied for Palestinian self-determination.

These are the victims whose devastated communities Australia’s Foreign Minister Penny Wong declined to visit during her trip to Israel in January.

**

Later this day the Israeli foreign ministry screened for our party of journalists the 47 minute video compilation of 7 October stitched together from Hamas body cams, CCTV footage and other sources. Four of us sat it out; three of us Jewish. I fretted over my decision. Did I not owe it to the victims to bear witness?

But as it is, the account of the two little boys in their underwear — covered in the blood of their slain father, one of them blinded in one eye, begging to be dead himself as a terrorist walks into their home and casually snatches a Coke from the fridge — as it is these two little boys stalk my waking hours. Did I really need to watch October 7 the movie? When I’m likely to be living October 7 forever?

The others emerged from the screening looking ashen; few slept properly that night. What lingered most, they told us, was the giddiness of the perpetrators, high on contempt for their victims.

**

Towards the end of our tour of Be’eri, the sun comes out. The air is fragrant with spring, the fields idyllic.

Some residents are returning to rebuild; older people and the young and childless. But families need to be convinced their children will wake safely in their beds come dawn.

From Gaza, not four kilometres away, we hear the buzzing of drones and thunder of artillery, foreboding the deaths of more children. Now and again the earth shudders gently beneath my feet.

We stop at the dental clinic; a makeshift triage centre on October 7, it was also where men from inside and outside the kibbutz made a stand, defending as best they could before the IDF’s belated arrival. A 22 year-old paramedic, Amit Man, tended to the kibbutz wounded before Hamas gunmen stormed in and shot her. For Israel, October 7 is an epic military failure in two parts: a failure of intelligence, and a failure on the day with the slow and chaotic IDF response.

“That day,” the Arab-Israeli journalist Lucy Aharish has said, “we were orphans.”

The dental clinic is more-or-less intact: dental chair, reception room, filing cabinets. Nili makes a sardonic remark to one of our Israeli guides but I don’t catch it. On a wall are scrawled tributes. One, in Hebrew, reads: “In memory of Amit Man, Eitan Hadad and Shachar Zemach who fought valiantly here.”

**

The bravery on display on October 7 was anarchic in nature. The moment images began flashing on the TV and internet of a breached border fence and armed men with green bandanas and white pick-up trucks tearing towards Israeli communities, reservists and soldiers grabbed weapons and charged out the door, without waiting for orders.

Among them was 33 year-old Salman Habaka. An IDF tank commander, Habaka drove three hours south from his home in the Druze village of Yanuh-Jat in the Galilee to Kibbutz Be’eri. Along the way he ordered part of his battalion to rapidly redeploy from Hebron on the West Bank, and so led two tanks into Be’eri, one of the first of the IDF forces to arrive. For the next 36 hours he killed dozens of terrorists and rescued civilians in intense house-to-house combat.

Then, on November 2, Habaka died in battle in northern Gaza.

His parents’ home in Yanuh-Jat is a shrine to their fallen son; portraits, banners of Habaka in uniform. On the coffee table is a model of a battle scene, a tank miniature festooned with a tiny Israeli flag.

The Druze are a small ethnoreligious group; there are about 15,000 in Israel. Their faith is Abrahamic and highly secretive and their cultural creed one of loyalty to their host country. Habaka’s father, Iman, extols his son’s patriotism and courage. “He is not like the terrorists, under the ground.”

In the corner, his wife, in traditional dress, weeps.

From the balcony outside the family home we trace the jagged ridge of the mountainous Lebanese border.

“Can you hear the fighting?” Iman asked, more in the nature of a statement: See how enemies surround us.

**

The Iranian-backed Hezbollah opened a new front of “Islamic resistance” on October 8.

Since then, Israel’s north has come under near daily attack with anti-tank missiles, drones and rocket fire. The IDF has retaliated, striking deep into Lebanon’s Bekaa Valley and assassinating Hezbollah’s chiefs in Lebanon and Syria. The hostilities have so far been calibrated to fall under the threshold of full-scale war, for which we can be thankful. The Shiite militia, deeply entrenched in southern Lebanon, has an arsenal of 150,000 warheads, including long-range precision missiles; a barrage could overwhelm Israel’s air defence systems and incinerate Tel Aviv.

“But you can’t evacuate everyone,” said a reservist we visited at a situation room 9 kilometres from the border. A former naval captain, he’s part of a local rapid response team. His manner was relaxed notwithstanding the M16 slung over his front, and khakis, which he says he only wears to calm the nerves of the small number of kindergarten children still in the area.

Around 80,000 residents are displaced from Israel’s north, most of them under official orders. Some remain to keep the orchards, farms and factories ticking.

The country now has two buffer zones within its borders and roughly 200,000 internal refugees. Many live in hotels otherwise empty of tourists, such as the one we stayed at in Jerusalem; the elderly, with their walkers, arguing and knitting in the lobby, the bleary-eyed mothers wrangling children. Their predicament has been described as a fundamental crisis of Zionism.

In the situation room, we ask the reservist if he feels safe.

“You never feel entirely safe in Israel,” he says. “There was a time in 2000 when you would not have driven behind a bus in Tel Aviv.”

**

Sarit Zehavi has certainly never felt entirely safe in Israel’s north; her work entails tracking the evolving security threats in the region, and she herself lives in the Galilee with her family. But even she experienced October 7 as a brutal wake-up call. On what should have been a sleepy morning during the Jewish festival of Simchat Torah, Zehavi’s phone started beeping urgent news. “Wake up,” she said to her husband, “this is war.”

A former IDF lieutenant-colonel in military intelligence, Zehavi in 2017 founded a strategic think-tank the Alma Research and Education Center, named after her newborn daughter.

On October 8, as Hezbollah launched its campaign of solidarity with Hamas, Zehavi pulled up a video of the Shiite group’s blow-by-blow plan to invade Israel. The terror group had published the video on its Al Mayadeen TV station a decade ago, but it had been years since Zehavi last watched it.

The invasion plan is telegraphed in helpful detail: a rain of missiles, the disarming of Israeli border surveillance, thousands of fighters from Hezbollah’s elite Radwan unit storming the border by land and sea, executions, the taking of hostages as bargaining chips. All of it sickeningly reminiscent of what played out on October 7. A dreadful realisation dawned on Zehavi; all these years she had assumed the worst-case scenario for Israel’s north was war.

“But now I know there is another worst-case scenario,” she tells us, “a massacre.”

At our visit to the Alma Center, Zehavi shows us footage of a funeral for Hezbollah fighters in a southern Lebanese village; ululating mothers chant slogans vowing revenge for the martyrs. We watch the video in a room with large windows looking out onto the green mountains of the Galilee. Grey clouds gather and disperse, the weather in this region frequently unsettled.

In the lead-up to Iran’s missile barrage on Israel in April and Israel’s stealth reprisal, the north held its collective breath for fear the Islamic Republic would activate Hezbollah as part of its attack. Zehavi spent the night of the attack with her family in their bomb shelter — it’s always stocked with food just in case, she told a Spanish news outlet. But all was quiet, relatively speaking, on the northern front.

Regardless: Hezbollah is a ticking bomb. A ceasefire agreement, Zehavi explains, will not disarm the threat; the militia is in breach of a 2006 United Nations resolution calling for the demilitarisation of southern Lebanon. The new Israel, hyper-vigilant following the ambush of October 7, figures the terror group is not amassing an arsenal or training tens of thousands of commando and combat troops as mere performance art. Six years ago the IDF discovered cross-border infiltration tunnels bored through the rock.

Absent a diplomatic solution, pundits had been predicting an Israeli offensive in southern Lebanon in the late northern spring or early summer when the tanks are less likely to get bogged down and by which time the Gaza operation would hopefully have been nearing completion. In May, Israel’s Defence Minister Yoav Gallant warned troops stationed in the north that they could be in for “a hot summer”; two months later he said the Israeli military would continue to neutralise the threat from Hezbollah even if a ceasefire is reached in Gaza.

Somewhat naively, I ask Zehavi why Hezbollah chooses to alert Israel to its invasion plans by broadcasting them to the world. She explained that the terror group thinks it can “break” Israelis through a thousand psychological cuts.

“They want to get Israelis on a plane out of the country.”

**

During our travels in the north, we drove through the town of Kfar Vradim. A flower bed on a traffic island spells the name of an absent resident, “Romi.” Romi Gonen, 23, is a hostage in Gaza.

**

We met with three hostage families. I will publish the names and recorded ages of the missing because we promised their stricken and desperate families we would do so. They are: Guy Dalal, 22, Doron Steinbrecher, 30, Karina Ariev, 19.

Between them, the families have harrowing stories of last phone calls, of hearing nothing and then seeing on Telegram an image of their loved one in the hands of gunmen. In January Hamas published a video of the two young women, along with a third hostage, Daniella Gilboa; the clip features pictures of the women on an animation of an hourglass. Doron is pale with sunken cheekbones. An image of Karina at the time of her capture shows her face swollen and crusted with blood.

Karina’s mother is from Ukraine; her father from Uzbekistan. Karina’s sister Sasha is five years older: she tells us her parents gave her a younger sister as a present. “We used to have a joke that I would die before her because I was older,” she says. “Now I say please let me die before my sister.”

My two daughters are five years apart. We had the second as a gift to the first. Across the room I see one of our journalists silently weeping, snot dripping from her nose. I realise I’m doing the same.

**

Grief, as we know, does not discriminate.

The Saturday before the start of a subdued Ramadan, I met with Ittay Flescher; a journalist and former high school teacher, who six years ago moved from Melbourne to Jerusalem.

We met up outside the Old City at Damascus Gate but couldn’t linger there as Israeli border police were moving people on. Ramadan is a time of heightened sectarian tension centred around the Al-Aqsa compound, Islam’s third holiest site, from where Muhammed is believed to have ascended to heaven and where the Jews’ sacred Temple also stood until the Romans destroyed it in 70AD, thereafter casting the Jews into exile before their miraculous return 2000 years later. In the end Ramadan passed without serious incident despite numerous provocations from Itamar Ben Gvir, one of the aforementioned Jewish-supremacists whose support Netanyahu relies on to govern.

When a month later I watched Iranian missiles flying over the Temple Mount I found myself imaging the holy sites vanishing in flames. Would this have consigned to history the zealotry and ancient hatred that blights the present?

Flescher introduced me to his Palestinian acquaintances working behind the counters at spice stores and bookshops in East Jerusalem. All said they were scaling down their festivities in solidarity with their wretched and hungry brethren in Gaza; some managed a pale joke about how there’s always too much food at these feasts anyway. All wore a sorrowful, haunted look.

“Just you watch,” said one with bitter resignation. “This shit show (in Gaza) will go on for another year.”

We walked through the contested neighbourhood of Sheikh Jarrah where a US-based Jewish settler organisation is seeking to evict Palestinian residents from a house — a long-running saga that the Israeli magistrates court last month described as a “simple real estate dispute.” In 2021, Hamas lent moral support to the Palestinian disputants through firing rockets at Israeli cities.

Flescher took me to a small room in what resembles a squat or a cave. I wandered inside to find devout Jewish women praying in front of what I later learned is the Tomb of Simeon the Just, a high priest of the Second Temple. As we’re about to leave a woman with a friendly, open face struck up conversation. She could “feel” I was Jewish, she said. She told us she was a poor, single mother but that every night she would sit on that bench — she pointed to a bench on a slight rise at the end of the street — and pray to God, and He delivered for her. Now she had a good job that meant she could support herself and spend time with her children.

“It makes sense she would think that way,” Flescher said afterwards. “She was a single mother with no support; from her perspective God was the only friend she had.”

The observation testifies to Flescher’s compassion. Among various pursuits, he is education director at Kids4Peace Jerusalem, an after-school program that brings together Jewish and Arab/Palestinian families to foster co-existence. About 80 families take part; the activities stopped after October 7 and are now resuming.

Over lunch at an Arab restaurant — few other restaurants being open on Shabbat in theocratic Jerusalem — we debated a two-state solution, one state solution, a confederation, the meaning of life. One comment of Flescher’s stayed with me.

“I say to my kids all the time, ‘you’re privileged to live in Jerusalem under Jewish sovereignty; because it’s rare in history for Jews to have sovereignty over Jerusalem, and we don’t know how long it will last.’”

**

One day we sat in a boardroom at Israel’s Defence Ministry headquarters in a skyscraper in north Tel Aviv. About half a dozen senior defence officials were speaking about Israel’s military challenges and initiatives. We journalists sat on one side of the table facing the officials. We each had a small cup of lemon tea and bowl of walnuts and dates. The officials were still and calm and softly-spoken. There were two women in the room, neither of whom spoke; one looked guarded and alert, the other in a constant state of amusement.

Calmly and methodically, the officials led us through a power-point of the objectives and frustrations of the war in Gaza, and the new and next-generation weaponry with which Israel would fight the coming war and the one after that. Tunnel-busting devices, drones, a laser-based missile defence system — or at least, I think that’s what they were. I’d picked up my pen to note it all down, but my hand froze in mid air.

I was spellbound by the way these people held themselves. Their stillness. Their quiet discipline in a room heavy with responsibility.

**

A former Israeli prime minister greeted us at his home. It’s a comfortable suburban home that would not be out of place in Melbourne’s leafier suburbs if not for the absence of a fence around the backyard pool, for the Jewish state is no nanny state. We sat at an outdoor lounge, looking over the garden and lawn. Someone outside our line of sight was playing catch with the family’s Boxer; over and over it ran and leapt across the grass in pursuit of an object.

The former prime minister began with a history lesson. He talked about the Jews’ two unsuccessful attempts at political sovereignty in the pre-modern era, both ending in internal disunity and external conquest. He said that in the Middle East non-Arab and non-Muslim peoples fare badly at self-determination; after all, neither the Lebanese Christians nor the Kurds managed to attain real sovereignty. Only the Jews have done that.

Maybe it was the angle of the late afternoon sun on the lawn, or the Boxer’s repeated running and leaping or the hypnotic quality of the former prime minister’s voice but I felt drawn, inexorably, to the melancholic conclusion that the odds of this current experiment in Jewish sovereignty lasting were grim.

I’d often heard my father invoking this curse of Jewish history to air his deep-seated anxiety that Jewish statehood was a doomed endeavour. Israelis would give it their best shot, of course. But the past can only repeat.

The former prime minister broke my reverie. This time — he assured us — the Jewish state is here to stay.

**

In Tel Aviv, on my first night in Israel, a Friday, I walked to a friend’s place for dinner. Having arrived in late afternoon, the taxi ride a long grind through traffic, I was not yet acclimatised to the wild pulse of this city, of this country. Every time I visit I experience an initial culture shock as the idealised Israel of my imagination collides with the exhausting reality of Israel.

It was a perfect night, mild, and the air still.

The stray cats darted about, the garbage bins over-flowing along with the bars and cafes; hedonistic disavowal, dancing through an apocalypse, has always been Tel Aviv’s ethos. Although in the first traumatic weeks after October 7 even this irrepressible city shut down.

I crossed “George Eliot Street” — a tribute to the author whose 1876 novel Daniel Deronda is hailed as an early acclamation of Zionism. I passed by the elegantly faded apartment blocks of the White City, the work of architects who fled Nazi Germany in the 1930s.

In these streets, the trees have grown to form a thick canopy of shade, a godsend in Israel’s scorching summers.

Every so often, a Pride flag draped from a window.

And it is here where I first see the Israeli flags with the love heart around the Star of David. Something inside me breaks. At some point over the next week I notice that the tightness in my chest that’s been there since October 7 is gone. That for the first time in months I’m breathing free air.

**

My friend lives in a quintessentially Tel Aviv apartment block. On this night he has set the table on the enclosed balcony. In the block across the street someone is playing the piano; the person is talented and persistent so it is as if we’re in a hotel lounge with jazz accompaniment. My friend, his wife and his brother are here, all working in the professions and the arts, three cherubic children between them. Only once the cherubic children finish their spaghetti bolognese and decamp to the couch for a movie, do I dare ask about the situation.

In the first weeks of the war, my friend said, when Hamas assailed Tel Aviv with rockets, they would sit on the balcony and watch the Iron Dome intercepting the missiles.

“It was like watching Star Wars every night,” he grinned.

My friend’s brother is bleary-eyed: he’d been on reserve duty the night before; it was eventful — he had to help from afar with an operation unfolding in Syria — so he didn’t get any sleep. We talk about the war, about how after October 7 Israel can no longer be reactive about the threats at its borders, about how Israel needs to come up with a “day after”(which is in fact today) plan for Gaza — “to give the Palestinians in Gaza some hope for the future,” my friend’s brother says. But, my friend says, the Netanyahu government is incapable of doing so and the Opposition is weak.

We talk about the pile-on against Israel.

“Do people ever think that maybe the journalists who are being killed aren’t really journalists?” my friend’s wife says, unprompted.

Earlier in the week the IDF had been accused of shooting hundreds of Palestinians as they gathered near Gaza City waiting to receive humanitarian aid, an incident dubbed “the flour massacre.”

“Well I watched the video,” said my friend’s brother, “and I can tell you the way it’s being reported is not what happened.”

“Look there’s this story in The New York Times, and the headline says there is ‘confusion’ about what happened,” said my friend, pointing at his phone. He chuckles. “Of course, it’s ‘confusing’ because how could it not be Israel’s fault?”

“Look, we’re far from perfect and then some. But the world is so interested in Jews.”

It is a theory much invoked since October 7, one eloquently put by the Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish who once told an Israeli interviewer that the Palestinians were “lucky” to have Israel as an enemy because if it was, say, Pakistan no-one would care.

My friend’s wife looked over at the three children huddled on the couch.

“We feel desperate,” she said, “I look at my kids and I wonder, when they grow up will there still be wars? ..”

The refrain is as old as the state of Israel.

I leave my friend’s place soon after the meal — everyone is tired. Me with jet-lag; them with the burden of their ordinary lives, and their shadow lives.

When I step out into the perfect Tel Aviv night, the jazz pianist is still playing.

**

I travelled to Israel as a guest of The Australia/Israel & Jewish Affairs Council (AIJAC).

One of my most long-standing observations of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is that the politicians on both sides are in power as a result of the conflict; hence they have an incentive for the conflict to continue. This is why the see-saw of uprising and punitive expedition has been repeating on a multi-decade cycle. Even if there was some circuit-breaker those in power have a perverse incentive to NOT allow it to take place.

I can't see Gaza ever returning to "normal". Outside the ideal but hard to attain outcome of full Hamas eradication the only viable option that assures Israel would be some kind of peacekeeping force taking over administration & security of the bailiwick.