One of the first things you notice on arrival at Helsinki airport — I’m recently back from a month in Europe — is a large ad boasting: “Our nuclear power plants provide a steady and reliable supply of electricity.”

This fact is incongruous with the headline on this piece so, to clarify: I won’t be tackling nuclear energy now or in the foreseeable future, the subject being outside my expertise. (I have a working knowledge of sex, however. So stay tuned.)

I mention Finland’s embrace of nuclear power because it’s an example of an admirable quality in the nation’s political culture. Nuclear energy is a contentious subject on which Europe is divided. Finland is in the French-led pro-nuclear bloc, but what’s interesting is the stance of its Green party. In May last year, it became the first in the world to back nuclear power as part of a plan to combat climate change. Not only are the Finnish Greens pro-nuclear, they’re fervently so: cheerfully advocating the cause to their counterparts overseas to an often hostile reception.

It is not the only example of Finland striking out on its own in a fraught area of policy. In 2020 the Scandinavian nation was the first to signal a more cautious approach to medical interventions for minors with gender dysphoria, replacing hormones with therapy as the first line treatment. Several other European countries have since followed Finland’s lead.

Both the Green party’s pro-nuclear pivot and the medical profession’s shift on affirmative care attest to a culture of dispassionate, evidence-based inquiry, resistant to pressure from activists wielding emotive slogans. Such a culture is exceedingly rare. It’s virtually non-existent in Australia: the treatment for youth gender dysphoria is politicised to the point of radioactive, and as for our own Greens, the mildest of internal dissent in its Victorian branch on trans issues sparked a Maoist crackdown, rearguard action and simmering civil war. The party is unlikely to engage in taboo-busting debate, about nuclear power or anything else, anytime soon.

Unfortunately, political progressives — including the progressive media that helps shape our cultural settings — struggle to get beyond this paradigm: nasty right-wingers support “X,” therefore “X” must be a bad thing. Or vice versa: nasty right-wingers are in a frenzy about “Y,” therefore “Y” must be a good thing, or at least a thing to be shielded from scrutiny.

A recent example of the latter is the controversy around Welcome to Sex, a 300-page illustrated guide pitched at teens aged 11 to 15.

***

For my overseas readers and those who missed the furore: the book made headlines after (mostly) conservative critics on social media whipped up outrage about its graphic content — anal sex, blow jobs, 69’ers, “rimming,” “scissoring” — alleging this was “sexualising” kids and making them vulnerable to “grooming” by predatory adults; the outrage was amplified by radio shock jocks thundering about WTS’ presence on the shelves at mainstream retailers Big W and Target, which reportedly led to employees at these retailers copping abuse, which led to the book getting pulled from the shelves of Big W, which caused a backlash against the backlash that led to WTS selling out on Amazon and bookshops running out of stock.

Our home-grown Trumpists are increasingly mobilising against what they perceive as threats to the moral order. This is an ominous development, to be sure. Whatever you might think about drag queen story time — personally, I find the concept mystifying and I say that as a fan of the drag — it’s rattling that the scheduling of such events in May led to threats and physical intimidation of council employees.

Amid the WTS storm, a 23-year-old New South Wales man has pleaded guilty to online harassment of one of the authors, Yumi Stynes. (Stynes’ co-writer is former Dolly magazine medical columnist, Dr Melissa Kang.)

Author and domestic violence campaigner Jess Hill told a Senate committee inquiry into consent laws in Australia that the WTS controversy was a reminder of the puritanical strain in the body politic that will continue to resist sex education initiatives; even as figures show almost half of Australian children aged between nine and 16 are regularly exposed to porn and its myriad harms.

But is the book itself any good?

For meaningful analysis I had to turn to social media. Twitter commentator “Jess” produced a comprehensive feminist critique of the book in the early hours of the controversy. Meanwhile, veteran cyber safety expert Susan McLean warned that the authors’ advice on sending nude photos was a dangerous misunderstanding of the criminal law that could potentially see minors snared for producing and transmitting child abuse material. (McLean had an op-ed published in the Nine papers some days later.)

What was McLean worked up about? Well, in discussing nude photos and sexting —which the book depicts as the contemporary equivalent of handwritten love letters — the authors write that if they were talking to their own children about sending nudes they’d advise them to crop their heads off “just in case,” because once a picture is out there you have no control over it.

This strikes me as strange advice to give teenage girls, overwhelmingly the recipients of requests for nudes though the book doesn’t explicitly say so. Apart from the depressingly foreseeable “guess the head on the body” scenarios in the boys’ locker room, why endorse this objectification? Why not gently suggest to our daughters that they’re more than a sum of their private parts and any guy worthy of their time should think likewise?

Then again, what do bodies mean anyway? The authors aren’t really sure. What does “boy” and “girl” mean? What even is this “sex” to which the book professes to welcome teenagers? “Sex is doing anything with your body that feels sexy,” the authors declare, and 15 or so years ago I might have happily agreed with them.

But this is a book drenched in gender identity ideology — an idea that has conquered our institutions virtually overnight. And this ideology renders everything to do with sex, including the act itself, unpindownable.

WTS has been compared to the definitive sex-ed books of my era, Where Did I Come From? and What’s Happening to Me? That’s sacrilegious. Where? and What’s? are warm, wholesome, adorably human texts: to this day, when I see teenagers mucking around at the local pool I think of the pic of that poor guy standing there with a boner amid bikini-clad girls.

Of course, WTS also has lots of body parts — and sound guidance on contraception, sexually transmitted diseases, respecting yourself and others, involving parents in decision-making. “Ghosting” someone post-sex is frowned upon; pubes are celebrated. (Right on!) The authors dispel the myth that everyone else is doing it. They allude to the complexities of lust. “How can I tell if it feels good?” reads one chapter heading. “..What about someone you kinda don’t like, who caresses your thigh in a way that feels good? What then?”

Teens are encouraged to masturbate; a positive message for girls given that boys need little encouragement — and a subject on which I’ve evangelised in the past.

So there’s plenty WTS gets right. Unfortunately it gets a lot more wrong and those things mostly stem from its flawed premise: a “fun, frank guide to sex and sexuality for teens of all genders.” (My emphasis.)

“We’ll use words like ‘person’, ‘teen’, ‘penis-owner’ or ‘vulva/vagina-owner’ most of the time,” the authors explain at the start. “On occasion we might use ‘girl/woman’ or ‘boy/man’ when we’re talking about cisgender people [people who aren’t trans] and referring to a specific question or story or research…”

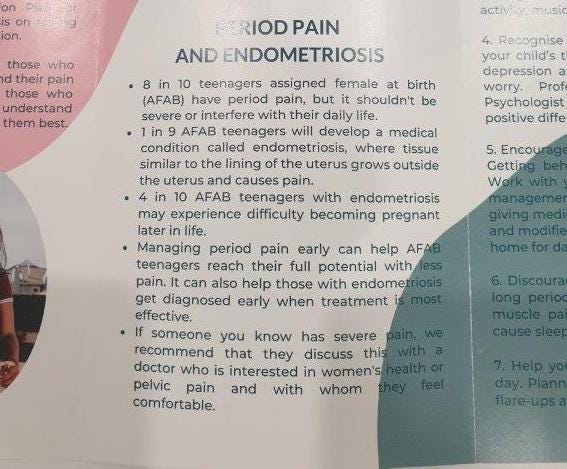

WTS has alienation from the sexed body as its default setting. It is a shockingly irresponsible message that can only fuel the social contagion of troubled teenagers declaring themselves “trans” to sometimes irreversible consequences. Still, this time everyone is doing it: no point singling out these writers for criticism when the (contested) notion of “gender identity” has seeped into classrooms. The worksheet below was distributed to Year 9 health and wellbeing students at a private girls’ school; notice it refers to teenagers “assigned female at birth.”

In WTS, we only intermittently glimpse boys and girls amidst the various “owners” of various body parts and genitalia. Orgasms can happen in “all sorts of bodies and all sorts of genitals,” we’re told. “It’s also fine to use words like ‘front hole’ for vagina.”

When a baby is born, the authors explain, one of the first things the parents or doctors do is look at its genitals.

“The adults surrounding the squawking, slippery little bub are often in a hurry to make a classification of its sex, and will usually decide that it’s female or male.”

Terrible how our overstretched health system forces such shortcuts, huh?

Some people, the authors continue, are born with an intersex variation in their reproductive or hormonal system. Here, the authors trot out the widely-aired estimate that 1.7 per cent of people have an intersex variation— “that’s almost two in a hundred!"

That statement would indeed merit an exclamation mark (they’re used liberally in WTS) if it was true. It isn’t. The figure is a sleight of hand on the part of gender ideologues to promote the idea that biological sex is itself a spectrum and not “binary.”

For an elegant demolition of this and other religious nonsense enter from stage left the evolutionary biologist and celebrity atheist, Richard Dawkins.

Recently Dawkins ignited passions on “TERF island,” aka the UK, with a piece in The New Statesman addressing the most improbably combustible question of the moment: “What is a woman?” Biological sex, he writes, is a rare instance of a “true binary.”

He explains the 1.7 per cent estimate for intersex conditions is “hugely” inflated because it includes Klinefelter and Turner syndromes, two genetic disorders, “neither of which are true intersexes,” because in both cases the individual’s reproductive sex is unambiguous. Remove these disorders from the equation, Dawkins says, and the real incidence of intersex shrinks from 1.7 per cent to less than 0.02 per cent.

“Genuine intersexes are way too rare to challenge the statement that sex is binary,” he says. Indeed, I’d argue they’re the exception that proves the rule.

Watch: Richard Dawkins in conversation with Helen Joyce, author of Trans: When Ideology Meets Reality

But, look — I can’t resist a side-bar here — the TNS “balanced” Dawkins’ piece with an essay from the renowned humanities professor Jacqueline Rose that argues “the gender binary is false.” Rose quotes approvingly trans writer Andrea Long Chu, who claims “female” was developed in the 19th century as a way of referring to black slaves. According to Rose, the notion that “female” is a neutral category is “historically naive and racially blind.” She must be taking the piss, you say.

Returning to WTS, sometimes it almost feels like the authors are taking the piss. For instance, “scissoring” is depicted with two topless women in their underwear mutually grinding at the genitals. One of the women is black and has one arm. The oft-satirised “black disabled lesbian” finally makes an appearance! Or maybe the image is intended to shame “historically naive and racially blind” white women into “doing the work”?

Elsewhere the book’s post-sex utopianism glosses over messy and inconvenient truths. The authors reject virginity as “a myth” that plays into a sexual double standard (correct) and assumes a heterosexual norm (also correct). But the hymen barely gets a mention. The authors don’t directly acknowledge that many young women experience pain and bleeding at their first experience of penetrative sex — it makes sense to choose a sensitive partner for the occasion.

Meanwhile the section on anal sex warns the practice is often painful and uncomfortable, and no-one should feel compelled to do it. I wanted the authors to explain the culpability of porn in normalising anal sex among heterosexual teens. Admittedly, this is a tricky dilemma: a teen sex guide that alienates boys will struggle for impact, if only because alienating boys is a terrifying prospect for most teenage girls.

In fact it’s striking that for all its daring and pretensions to inclusivity, WTS has no explicit images of gay male sex. Perhaps that would be too much for het guys? While there are personal stories of gay males “coming out”, same-sex attraction is portrayed as one in a smorgasbord of “identities,” all of which the authors frantically validate, including anti-identities, such as “agender” and “aromantic.” No surprises here: an ideology that seeks to blur the reality of biological sex will inevitably peddle soft homophobia.

Is WTS a potential “grooming” manual for paedophiles, as some of its wilder detractors claim? I’d say that’s hysterical nonsense. Paedophiles, as we know, are just as likely to target children ignorant of sexual matters as they are precocious children so long as they perceive the children as vulnerable.

What of the related accusation that WTS is part of a global movement to “sexualise” children? Whether such a “global movement” exists is a question that deserves an expansive answer, so I’ll return to the theme another day. (Perhaps once I figure out the rationale behind drag queen story time.) In this instance, the authors insist that it’s the ubiquity of porn that’s sexualising children; they’re simply trying to counter porn’s damaging effects.

Well, I’m not sure that giving adolescents a how-to manual on “rimming” and blow-jobs — “you can move your mouth and tongue up and down the penis, or put it in your mouth and move your mouth up and down on it” — is an effective counter to porn’s fixation on mechanics.

As for Stynes’ remark that WTS might be suitable for a “mature 8 year-old” — talk about a spectacular own-goal.

***

“Sexualising” kids is one danger: turning them into sex phobics is another.

During my mid-teens I would occasionally babysit for a relative whose house heaved with books. A friend usually came too, and once our charges were asleep we would rush, sniggering and whispering, for one book displayed nonchalantly on a shelf: The Joy of Sex, the 1972 illustrated sex manual by the aptly named Dr Alex Comfort. (If you’re a long time reader of my work and this anecdote sounds familiar; I indeed shared the memory 15 years ago on the release of an updated version of Joy.)

We would turn the pages in fascinated horror— ‘‘Oh, yuck!’’ ‘‘Oh, my god!’’ ‘‘I don’t get it — what’s he. . . where’s her . . .?’’ — as a shaggy-bearded man and curvy woman with full bush explored a “cordon bleu” sexual menu from “appetisers” to “main courses,” “sauces,” the “Viennese oyster,” and beyond. But even as my pubescent self expressed revulsion, I could glimpse in the book’s pages an uninhibited adult world in which sex was indeed something joyful. I was able to make this concession to my future self precisely because the book was not aimed at teenage me. Joy was a missive from a faraway land that I was in no hurry to reach.

Our kids are having to navigate their own, uniquely turbulent, passage to adulthood, as boys and girls, men and women, males and females, irrespective of the labels they adhere to on any given day. And more than ever they need us adults — parents, teachers, policymakers — to guide them safely to the other side; but instead of doing that, and I’m sorry to end on this note, we’re disappearing up our own orifices.

Really interesting post, thank you. I've only seen screenshots of parts of the book but was struck that the section about sexual orientation had nothing much to say about human relationships and chemistry between people. Nor did it do the 1990s message to same sex attracted teens of "You're feeling a lot of feelings at your age, that's normal, so don't worry, take your time, hang out with good friends and don't feel pressured - maybe you'll turn out gay, maybe not, but you'll be fine either way and you'll always have people who love you". It might have been cheesy but it reassured us! Instead this book encourages teens to ruminate endlessly on their own inner "identity". Seems a recipe for dysphoria and loneliness amongst anxious teen girls.

I meant to add: I really like the distinction you make between Gen X kids sneaking a look at some hippie parents' copy of The Joy of Sex, knowing it was definitely meant for adults, versus kids nowadays having this stuff written for and handed to them. Developmentally, I think it's a very different experience.